Research, services lacking for autistic Indigenous people, say researchers

The formula seems simple: Take evidence-based research, add patient input and highly trained professionals plus adequate resources, and you get accessible, appropriate health care.

But what if there’s no data on the patients or their needs, few trained professionals and no agreement on the best model to deliver care?

That’s the situation for autistic First Nations, Métis and Inuit people, according to a new national report assessing autism services across Canada.

All of the barriers non-Indigenous autism patients face—and they are considerable—are exacerbated by colonization and related intergenerational traumas and leave Indigenous autistic children, adults and their families in limbo, say two researchers in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry who are working to help fill that gap.

“Our primary conclusion is that to substantially address these issues, the work needs to be Indigenous-led,” says Lonnie Zwaigenbaum, pediatrics professor, director of the Autism Research Center and chair of the national report completed by the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences at the request of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

“The report was predicated on the ability to integrate existing evidence with lived experience, and the reality is there’s just not a lot of published evidence in this area,” Zwaigenbaum notes.

Grant Bruno, parent of two autistic boys and a member of Nipisihkopahk (Samson Cree Nation), is a Ph.D. student studying autism within First Nations communities in Alberta and served on the Indigenous advisory committee for the report. He says it’s not surprising there is little community-based research available.

“Colonialism, poverty and all the trauma that came from residential schools mean our communities are in survival mode. And if you’re in survival mode, you can’t pursue grad school and research, because you’re worrying about groceries or the boil-water advisory,” Bruno says. “I’ve been trying to get more opportunities for our communities to engage in research in really good ways.”

Missing data

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition that affects sensory processing, communication and behavior. About two percent of the Canadian population has ASD, according to the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth from 2019, although families on First Nations reserves were not included. Prevalence studies are usually the first step in planning for services, according to Zwaigenbaum.

“It’s notable that the most recent Canadian data on autism prevalence specifically excluded families that were living on reserve, so there’s a perpetual gap in knowledge, even of the basics of how many children need to be supported,” says Zwaigenbaum, the Stollery Children’s Hospital Foundation Chair in Autism and a Stollery Science Lab Distinguished Researcher.

For the national study, Zwaigenbaum and his team reviewed 6,500 research papers and received input from nearly 1,700 autistic people, along with nearly 1,500 family members. The goal was to inform the federal government on gaps in research and services for autistic Canadians, with an emphasis on equitable access to diagnoses and health care, inclusion in education and employment opportunities, and ways to address stigma.

The report’s authors concluded that while each of the hundreds of First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities in Canada is different, there are “unique inequities” experienced by most Indigenous people, including difficulty accessing culturally responsive, evidence-informed diagnosis and services, especially in rural or remote communities. On-reserve health care is the responsibility of the federal government, but most autism services are delivered by provincial health authorities.

Mistrust and misdiagnosis

Bruno currently resides in Edmonton due to the lack of services for his children on reserve and travels to Maskwacîs weekly for his research and to stay connected with his culture. He notes that families in his community usually have to travel to the city to have their children tested and diagnosed. Often First Nations autistic children are misdiagnosed with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) due to biased training and assumptions on the part of health-care professionals, Bruno says.

“A lot of Indigenous health research is deficit-oriented,” Bruno says. “And so when you’re reading this over and over and over again, you start to build up certain stereotypes towards Indigenous people, that we’re all alcoholics or we’re all dealing with some sort of addiction. I’ve even heard we have a different pain tolerance, which is completely untrue.”

Bruno, whose work is supported by the Stollery Children’s Hospital Foundation through the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute, found only 20 evidence-based research papers about autism within First Nations, but thousands on FASD. He discussed the implications of this on a podcast entitled, “The Realities of Autism in First Nations Communities.”

Difficulty with access and fear of bias means some families refuse to have their children tested. Bruno lauds the Maskwacîs Education Schools Commission for providing specialists like speech-language pathologists and occupational therapists to work with children who don’t have a diagnosis. The downside is that going without a diagnosis may limit those children’s access to services once they become adults.

Both Zwaigenbaum and Bruno say the broader community has much to learn from the approach to autism taken by some Indigenous communities, where each child is viewed as a gift and autism is seen as a different way of thinking rather than a deficit-based disability.

“One thing my community does really well is autism acceptance, much better than anybody else in Canada,” says Bruno. “I’m trying to share that message because when I talk to the autistic community more broadly, they say, “I identify more with that than the deficit-oriented medical model that’s often pushed on us.”

“When you talk to autistic people, they just want to be themselves. They don’t want to be changed into something else.”

Zwaigenbaum sees this approach as strengths-based and focused on inclusion of neurodiversity.

“There are themes that Grant has identified around appreciation of differences and the importance of community leadership, building trust and empowerment that resonate for all autistic individuals and families,” Zwaigenbaum says.

Building strengths through culture

Bruno has set up an autism advisory circle for his own research that includes Elders, autistic people, service providers and educators. One of its projects is to organize a sensory-friendly round dance for next year. Bruno stresses that such culturally appropriate services are needed for autistic Indigenous people and their families.

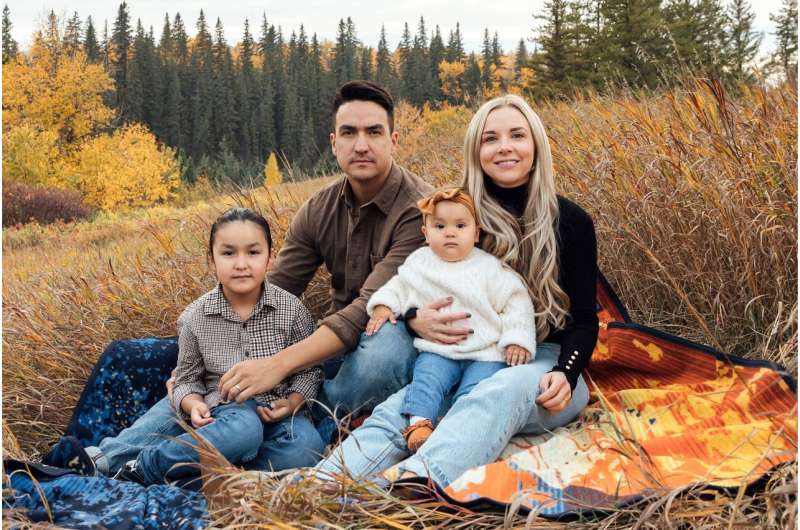

He sees the power of his Nehiyaw (Plains Cree) culture every morning in his living room. Before serving breakfast to his four children, he lights sage for a smudge. Sitting in a circle, each child takes a turn holding an eagle feather and praying aloud. When it is seven-year-old Anders’ turn, the boy says, “I want to pray for Mom and Dad and my brothers and my sister and nôhkom (my grandmother) and nimosôm (my grandfather) and myself.”

Until recently, Anders—who was diagnosed as autistic at age four—didn’t communicate verbally. His words sounded like gibberish to his father. But with support from his parents and specialists, and immersion in cultural practices such as ceremony, powwow dancing and drumming, he has started using full sentences.

“When he’s speaking with that feather in his hand, he does it a lot longer,” says Bruno, whose 12-year-old son Marshall is also on the spectrum.

Source: Read Full Article