Sepsis History

Sepsis is a potentially fatal condition in which the body has a systemic inflammatory response to an infection. The history of sepsis stretches back to ancient Greece, but it is still a serious condition that is difficult to treat today.

Sepsis: the beginning

Sepsis was first mentioned by scriptures in Ancient Greece. The word sepsis comes from the Greek word “sepo”, which means “I rot”, and has its first use in medical context in Homer’s poems.

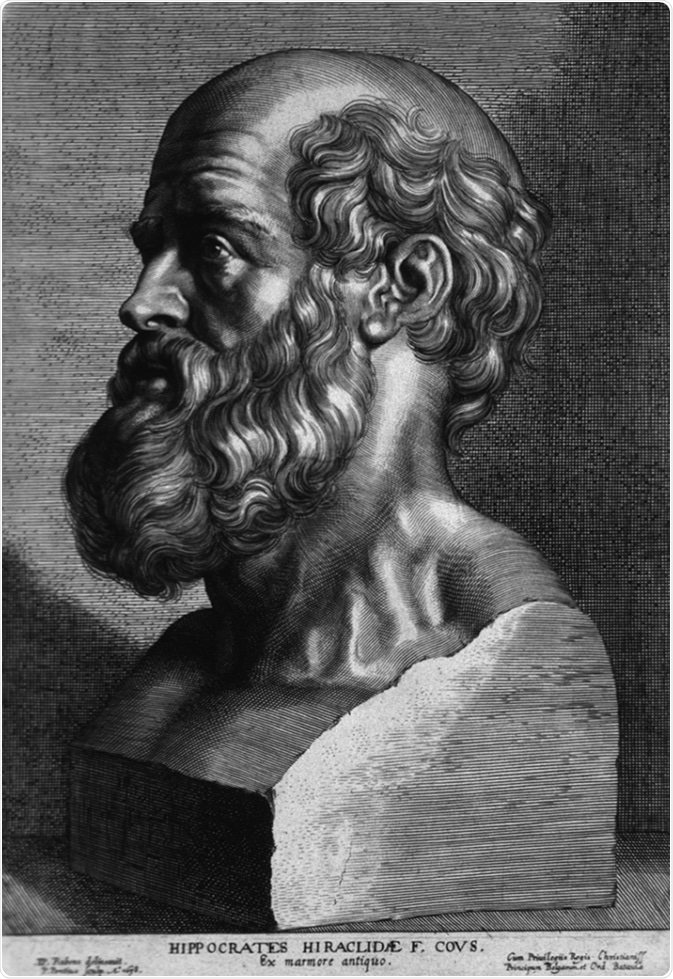

It is also mentioned in the writings of Hippocrates, a physician and philosopher, around 400 BC. He viewed sepsis as dangerous biological decay that could potentially occur in the body.

It is also mentioned in the writings of Hippocrates, a physician and philosopher, around 400 BC. He viewed sepsis as dangerous biological decay that could potentially occur in the body.

Biological principles of disease were not well understood, so the decay in sepsis was believed to occur in the colon and release various substances which caused “auto-intoxication”.

Hippocrates tried to find a pharmacological response through antisepsis properties in alcohol in wine and vinegar.

After Hippocrates, in 129-199 AD, Galen, a respected Roman physician, and philosopher, theorized about sepsis.

He was a pioneering pharmacologist who developed the precursor for the apothecary and developed theories about wound healing and pus which lasted for 1500 years.

Regarding sepsis, Romans believed that the syndrome resulted from invisible creatures that gave off fumes. These creatures created the foundation of the Roman public health system, emphasizing hygiene practices.

In a way, the Romans were correct. Sepsis is developed as a result of an infection, which can come about as a result of poor hygiene. However, they never considered transmission by person to person contact, and therefore missed the general theory of infectious disease.

Sepsis in the 1800s

At the start of the golden age of germ theory, Ignaz Semmelweiss made monumental observations about puerperal sepsis, or sepsis that occurs after childbirth.

He noticed that in his ward, women who had assistance from midwives during delivery developed puerperal sepsis 2% of the time, whereas those who had help from medical students developed it 16% of the time.

As a result of a colleague dying from an infection acquired during an autopsy when he accidentally cut himself, Semmelweiss was able to recognize that the reason medical students could influence the chances of developing puerperal sepsis was because they would perform autopsies and deliver babies without washing their hands.

He instituted a policy forcing the medical students to wash their hands before seeing a patient and saw the rates of puerperal sepsis reduce to below 3%. Unfortunately, it appears he was a pioneer of this idea of basic hygiene, as his policy was met with heavy criticism and he was fired.

Soon after Semmelweiss, Joseph Lister, Louis Pasteu r and Robert Koch did their seminal work in furthering our understanding of microbiology and infectious disease.

r and Robert Koch did their seminal work in furthering our understanding of microbiology and infectious disease.

While many aspects of infectious disease are pertinent to sepsis, some of these works stand out more.

As a result of Pasteur’s experiments disproving the theory that diseases developed spontaneously, Lister formalized his theories on wound sepsis.

By realizing wound sepsis occurred due to pathogens entering the breaks in the skin, he developed dressings with carbolic acid which led to a significant decline in wound sepsis and associated death in his hospital.

Recent developments

The past 30 years have seen an increased focus on how to better understand and treat sepsis. In the early 1990s, a conference was held to come to some kind of consensus as to what sepsis was defined as.

This was modified by the 2001 conference but ultimately lead to the development of a distinction between an infection, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock.

1900s

In 1964, a Boston surgeon called Dr. Edward Frank published a management strategy for septic shock.

The strategy included continuous monitoring of systemic arterial pressure, central venous pressure, cardiac output, urinary output, blood volume, blood chemistries, gases, pH, and electrolytes.

Some of these, such as blood monitoring and urinary output, are still used today.

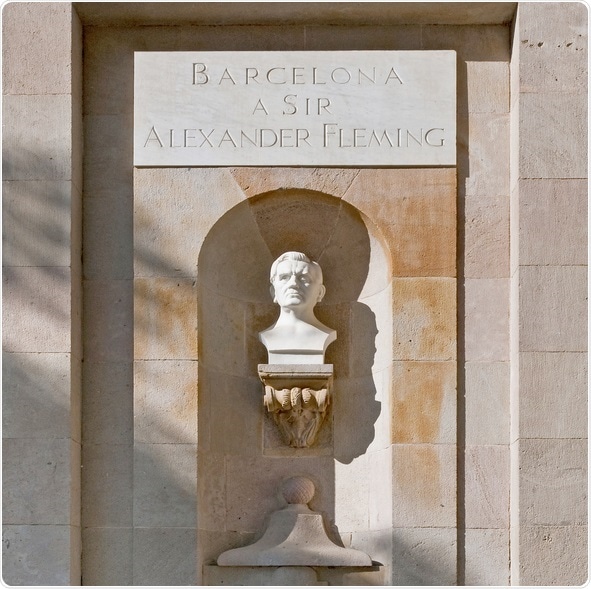

He also recommended finding the cause of the infection, which is still done today, aided by the discoveries of antibiotics by Alexander Fleming earlier that century.

However, Dr. Frank also recommended antiadrenergic drugs and correction of electrolytes and acid-base balance, which are not used today.

2000s

In 2003, the modern guidelines for severe sepsis and septic shock were published by an international committee.

It was updated in 2012 and includes some of the same principles outlined in 1964: cardiac resuscitation, identifying the pathogen to start targeted treatment, and support for the respiratory system.

Newer management techniques included volume resuscitation with crystalloid, use of stress dose steroids when sensible, oxygen delivery, and recognition and management of dysfunction of the central nervous system.

Sources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16239619

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19268796

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1522840114000445

Further Reading

- All Sepsis Content

- Everything You Need To Know About Sepsis

- Sepsis Diagnosis

- Causes and Symptoms of Sepsis in Newborns

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Sepsis in Newborns

Last Updated: Sep 11, 2018

Written by

Sara Ryding

Sara is a passionate life sciences writer who specializes in zoology and ornithology. She is currently completing a Ph.D. at Deakin University in Australia which focuses on how the beaks of birds change with global warming.

Source: Read Full Article