Shortage of critical cancer drug forcing some children to go without

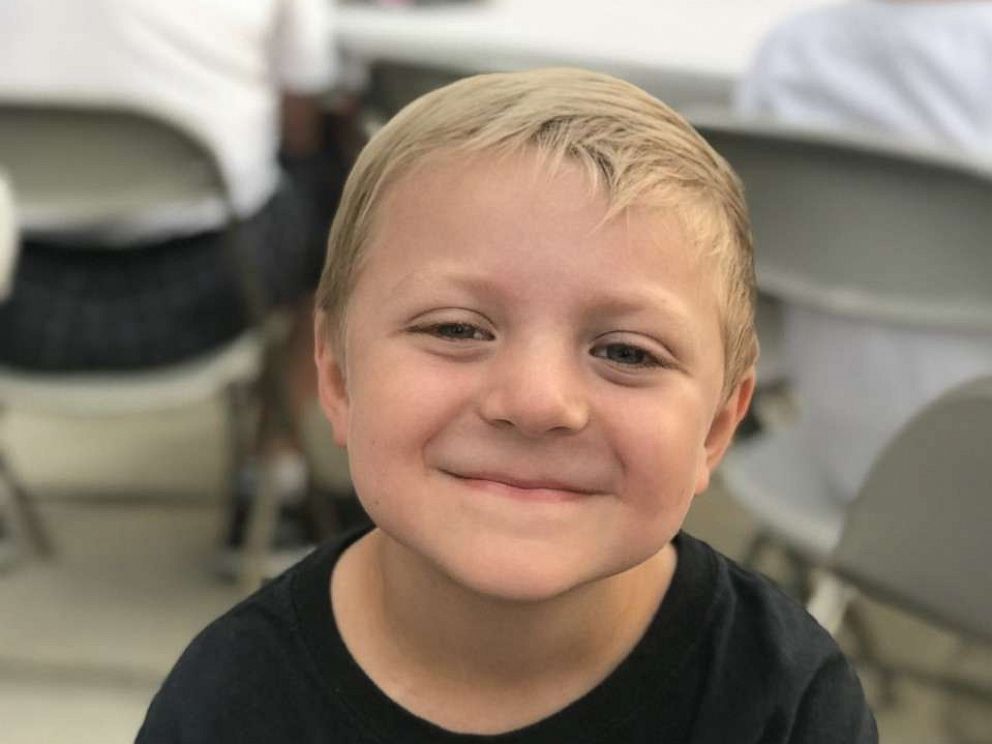

When 4-year-old Milo Sligh, of Charleston, South Carolina, was diagnosed with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia the word “cancer” was frightening, but the prognosis was hopeful, according to his mother, Marisa.

The diagnosis of a childhood cancer is a life-changing and highly emotional experience for families and the affected child, but the chemotherapy medication vincristine is a tried and true regimen effective for treating many childhood cancers, including leukemia, lymphoma and brain tumors. But instead of the simple remedy, the Slighs — and many other families — fears’ are multiplied now that the low-cost, generic medication is in short supply and doctors have started rationing its usage.

The shortage is especially frightening because there is no known drug available that is equally effective.

“We are greatly concerned that some children are already being impacted by this shortage and by the understandable anxiety this creates for all families of children with cancer,” Dr. Peter Adamson, chair of the Children’s Oncology Group, said in an open letter to the childhood cancer community just days ago. He went on to say this is “an unacceptable crisis” and he is “infuriated that this situation has occurred at all.”

“Every child with cancer whose treatment requires vincristine should receive the drug as scheduled,” he added.

A petition on WhiteHouse.gov has over 73,000 of the 100,000 signatures required in 30 days to get the White House to respond. The petition includes language like, “Our children are going to start relapsing and dying at higher rates if we do not do something about this shortage immediately!”

Earlier this month, pharmacists started raising concerns about the ability to obtain vincristine. Pfizer, now the only supplier of the drug in the U.S., reported experiencing a shortage due to manufacturing delays. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Teva Pharmaceuticals made “a business decision” to stop supplying the medication in July 2019.

Kelley Dougherty, vice president of corporate communications for Teva, told ABC News in a statement the company “alerted the FDA of its decision [to stop manufacturing vincristine] in March 2019.”

Pfizer told ABC News in a statement, “We are expediting additional shipments of this critical product over the next few weeks to support three to four times our typical production output.”

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is the most common childhood cancer, impacting about 3,000 children a year, most aged 2 to 5 years old. It occurs when the bone marrow makes too many immature white blood cells. Symptoms may include fever, fatigue, easy bruising, bone pain, bleeding from the gums, swollen lymph nodes and frequent infections. Children need to be treated quickly with chemotherapy once a diagnosis is made.

In addition to chemotherapy, treatments can include radiation and targeted therapies, and “around 98% of children with ALL go into remission within weeks after starting treatment and about 90% of those children can be cured,” according to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Patients are considered cured after 10 years in remission.

Milo has responded well to his treatment, but Marisa worries that she may be told he can’t get vincristine at his appointment in two months because of the shortage.

“Every time a dose is missed his chance for cure is decreased,” she said.

The FDA says on its webpage that it expects vincristine to start shipping by the end of October and supplies will reach recovery levels by January 2020.

“We are working closely with [Pfizer] and exploring all options to make sure this critical cancer drug is available for the patients who need it,” the FDA said in a statement to ABC News.

Marisa is anxious because of the posts on her tight-knit Facebook group from other families who have not received vincristine, or got a smaller dose than usual.

Laura Brewer is part of the Facebook group for parents of children with ALL. She lives in Kansas City, Missouri, and her 5-year-old son, Titus, also has acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is in remission. She said his appointment for treatment next Thursday will not include vincristine, because the doctors told her they need to ration it, perhaps for someone with a newer diagnosis.

“It is terrifying as a mom that a drug your child needs is not available,” Brewer said.

Her biggest fear for Titus after turning the corner is that his cancer will return: “You pray and hope to God nothing shows up [in future testing].”

Vincristine has been on the market since 1963 and is a staple drug in the treatment of ALL, but most kids will need to get intravenous infusions of vincristine for two to three years for maintenance treatment to keep them in remission.

Dr. Damon Reed, adolescent oncologist at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, said that vincristine is used in “greater than 50% of cancers in pediatrics” and “fewer than 3% of adult cancers.”

“Every [hospital] has a vincristine story,” Reed remarked.

Without refills arriving to their center soon, Reed said his cancer center may run out by November or December. Drug shortages force doctors and pharmacies to ration drugs, which is never beneficial for all patients. He said that he has experienced several cancer drug shortages in his years of practice. The reason may be because the tried and true generic medications aren’t very profitable.

In his open letter demanding action, Adamson said that the frequency of drug shortages has increased in the past 10 years.

According to FiercePharma, “With margins on generics having gotten very thin in recent years, many drugmakers have given up production of products where they are not dominant in the marketplace. There are currently 202 drug discontinuations listed on the FDA Drug Shortages website.”

One potential reason was the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003, which capped the amount that hospital systems are reimbursed for intravenous cancer drugs.

Dr. Roger Bate, a scholar at the think tank American Enterprise Institute said there is a “lack of competition” among manufactures because of the historical “slowness of the FDA [generic] approval process.” Lack of competition means that there are fewer suppliers and consumers are dependent on one company, or a few, to get the drug. Another reason may be that “manufactures are not making enough profit” and some drugs “are too cheap.” The average price for vincristine is “about $5,” according to Adamson.

Bate also noted that generics, or bioequivalents, frequently face issues with quality control, which makes it difficult for companies to continue to produce the product. As a result, they may stop making the drug and shortages happen.

Dr. Marty Makary, author of “The Price We Pay,” said “flimsy supply chains” can create drug scarcity. An illustration of this was the normal saline deficit that affected the entire country after the destruction of factories in Puerto Rico during Hurricane Maria. The FDA formed the Drug Shortages Task Force in July 2018 in response to increased drug shortages. They hosted a public meeting in November 2018 to perform a root-cause analysis and developed immediate and long-term strategies for these situations.

The hope for Milo and Titus is that their survival will not be impacted by the current shortage of vincristine, but the drug is only one example of the current problem the U.S. is facing in regards to generic drug manufacturing and shortages.

“While we are infuriated that this situation has occurred at all, we should do our best to have advocacy efforts stay focused on solutions,” which may include short-term importation from other countries, according to Adamson.

“I am hopeful we can take this unacceptable crisis and move toward better answers, always keeping the interests of patients and families central to our efforts,” he added.

For any family that is currently having difficulty obtaining vincristine for their child, the FDA recommends that you contact them at [email protected].

Sherise Chantell Rogers MD, MPH is an Internist and Hematology & Oncology Fellow at The Ohio State University Medical Center, and a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.

Source: Read Full Article