Researchers track cellular and antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccine

In a technical tour de force, a collaborative team of Vanderbilt researchers has characterized the antigen-specific immune response to the Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 RNA vaccine.

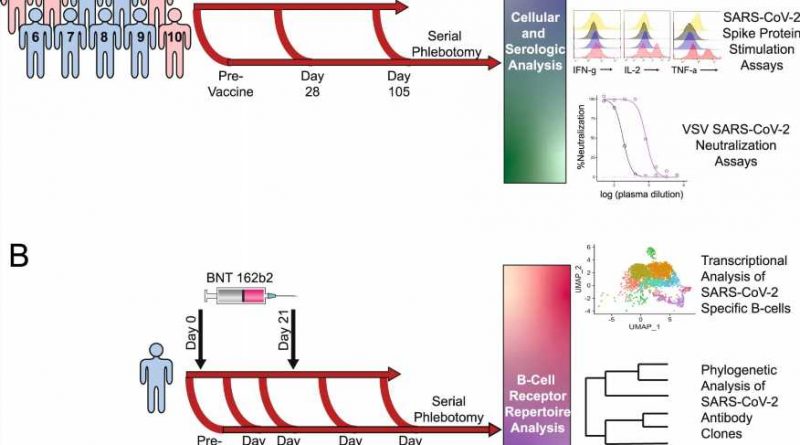

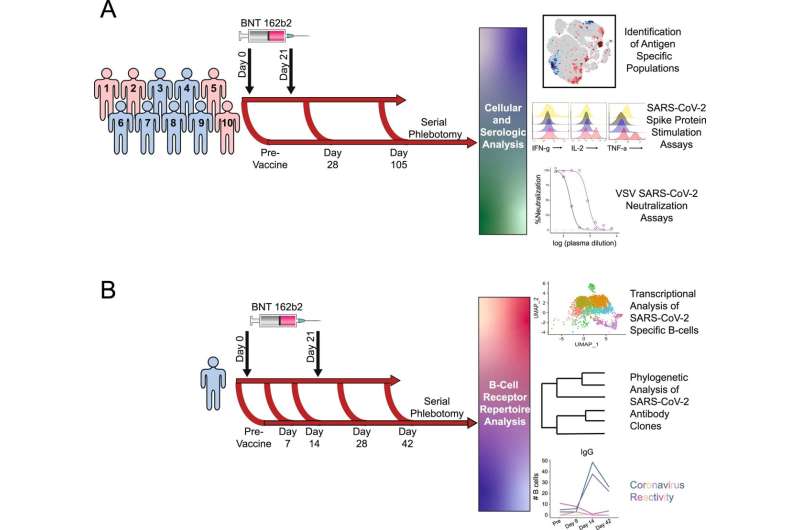

The group used multiple single-cell technologies, unbiased machine learning, and traditional immunological approaches to track cellular and antibody responses in samples collected over time from a cohort of healthy participants. The findings, published in Nature Communications, could guide testing for vaccine response and booster timing.

“There is a lot of debate in the clinical immunology field about what is an appropriate vaccine response: What actually protects someone against disease?” said Erin Wilfong, MD, Ph.D., instructor in Medicine and one of three co-first authors of the paper with Kevin Kramer, Ph.D., and Kelsey Voss, Ph.D. “How do we know who’s had a good response, and who hasn’t? How do we know when people need a booster?”

When VUMC began vaccinating its workforce against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in December 2020, the collaborative team was in a unique position to explore these questions.

The researchers—including the groups of Jonathan Irish, Ph.D., Ivelin Georgiev, Ph.D., Rachel Bonami, Ph.D., and Jeffrey Rathmell, Ph.D., all co-senior authors of the Nature Communications paper—had been working together through the Human Immunology Discovery Initiative (HIDI), which was funded in 2019 by a Vanderbilt Trans-Institutional Programs (TIPs) award.

“The TIPs grant brought together researchers with disparate technologies and expertise focused on trying to understand how the human immune response works,” said Rathmell, director of the Vanderbilt Center for Immunobiology, which coordinates HIDI.

Kramer, who was a graduate student in Georgiev’s lab, suggested that the group study the response to the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy volunteers who had not had the disease COVID-19.

“It’s challenging to find a setting where you can study the human immune response to something new,” Rathmell said. “This was an opportunity for us to see what happens for the very first time with an entirely new class of vaccines, the RNA-based vaccines. From a basic science standpoint of ‘What do these vaccines do?’ that was very interesting.”

Within hours of getting Institutional Review Board approval and sending out an email to a faculty list, the team had volunteers ready to donate blood samples ahead of being vaccinated, and several times afterwards.

Irish and Georgiev have both pioneered single-cell technologies and unbiased analytical approaches to find and identify the rare immune cells directed at specific antigens—in this case the SARS-CoV-2 viral spike protein. Bonami is a B cell biologist who developed single-cell analytical pipelines to identify which of the functionally distinct subsets or “flavors” of antigen-specific B cells expanded with vaccination.

Using these technologies alongside other single-cell and traditional approaches, the group identified and characterized the SARS-CoV-2-directed B cells that instruct T cells and produce antibodies and the T cells that can kill virus-infected cells and also help direct antibody production.

“Right now, the way that we test if vaccines are working is by measuring antibodies,” Rathmell said. “You really need both antibody-producing B cells and T cells for an effective immune response, and we’re not measuring either of the cells.”

The team was able to develop strategies for using a more common technology—flow cytometry—to find the B and T cells that respond specifically to the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

“We’re still a long way off, but this is a first step towards being able to test whether someone had a good cellular response,” Wilfong said.

The researchers expect such measurements will be useful, particularly for determining the vaccine response of high-risk individuals and for defining if and when booster doses might be beneficial.

One of the participants who did not have the identified vaccine-induced cell populations had a breakthrough COVID-19 infection, they reported.

The group was also intrigued that the vaccine-induced T cells they identified had unique characteristics that didn’t match previously described categories of T cells.

“I think we found a new phase in an immune response,” Rathmell said. “It’s going to be an interesting set of cells to study in the future. These cells are the ones that correlate best with the antibody response.”

Source: Read Full Article