Immunotherapy combo achieves reservoir shrinkage in HIV model

Stimulating immune cells with two cancer immunotherapies together can shrink the size of the viral “reservoir” in SIV-infected non-human primates treated with antiviral drugs, researchers have concluded. The reservoir includes immune cells that harbor virus despite potent antiviral drug treatment.

The findings, reported in Nature Medicine, have important implications for the quest to cure HIV, because reservoir shrinkage has not been achieved consistently before. However, the combination treatment does not prevent or delay viral rebound once antiviral drugs are stopped—illustrating how difficult achieving a cure will be. Monkeys infected with SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus) are considered to be the best model for HIV infection in animals.

“It’s a glass-half-full situation,” says senior author Mirko Paiardini, Ph.D. “We concluded that immune checkpoint blockade, even a very effective combination, is unlikely to achieve viral remission as a standalone treatment during antiretroviral therapy.”

He adds that the approach may have greater potential if combined with other immune-stimulating agents. Or it could be deployed at a different point—when the immune system is engaged in fighting the virus, creating a target-rich environment. Other HIV/AIDS researchers have started to test those tactics, he says.

Paiardini is an associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and a researcher at Yerkes National Primate Research Center. The study was performed in collaboration with co-authors Shari Gordon and David Favre at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and GlaxoSmithKline; Katharine Bar at the University of Pennsylvania; and Jake Estes at Oregon Health & Science University.

“This was a very complex study and we are especially thankful to veterinarians and animal care staff,” Paiardini adds.

Although antiviral drugs are available that can suppress HIV to the point of being undetectable in blood, the virus embeds itself in the DNA of immune cells, frustrating efforts to root it out. Only two individuals have ever achieved what their doctors consider a durable cure, and they went through a bone-marrow transplant for leukemia or lymphoma—not widely applicable.

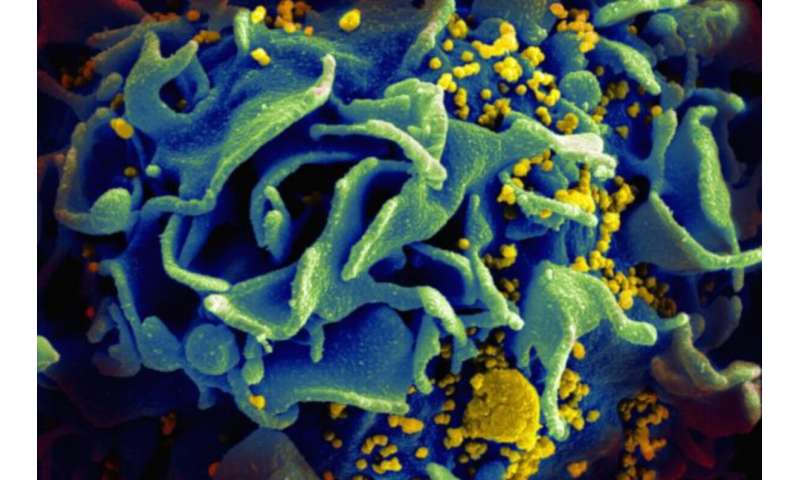

Paiardini and his colleagues reasoned that chronic viral infection and cancer produce similar states of “exhaustion”: immune cells (T cells) that could fight virus or cancer are present, but unable to respond. In long-term HIV or SIV infection, T cells harboring the virus display receptors that make them targets for checkpoint inhibitors, cancer immunotherapy drugs that are designed to counteract the exhausted state. In the context of HIV infection, these types of drugs have been tested to a limited extent in people living with HIV who were being treated for cancer.

In the Nature Medicine paper, the researchers used monkey biosimilar versions of ipilimumab and nivolumab, which block the inhibitory receptors CTLA-4 and PD-1, respectively. In monkeys that received both CTLA-4- and PD-1-blocking agents, researchers observed a stronger activation of T cells, compared to only PD-1 blockade. DNA sequencing of viruses in the blood revealed that a broader range of viruses were reactivated with the combination, compared to single checkpoint inhibitors.

“We observed that combining CTLA-4- and PD-1 blockade was effective in reactivating the virus from latency and making it visible to the immune system,” Paiardini says.

In previous studies, limited shrinkage of the viral reservoir has been seen only inconsistently with single checkpoint inhibitors or other immune-stimulating agents. Only combination-treated animals showed a consistently measurable and significant reduction in the size of the viral reservoir. This was measured with “DNAscope”, an imaging technique to visualize infected cells within tissues, and by measuring the frequency of CD4 T cells, the main targets of HIV and SIV, harboring intact viral DNA.

Despite this effect, once antiviral drugs were stopped, the virus still came back to the same level in combination-treated animals.

“We believe this is due to having much less viral antigens around after long-term antiretroviral therapy, compared with the situation in cancer,” says Justin Harper, lab manager and first author of the paper. “This makes much more difficult for the immune system to recognize and kill those cells.”

A note of caution: the equivalent combination of CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade in humans has been tested in the context of cancer treatment. While the two drug types can be more effective together, patients sometimes experience adverse side effects: severe inflammation, kidney damage, or liver damage.

Source: Read Full Article