DR MICHAEL MOSLEY: My brilliant BBC friend Jana and her brain cancer

DR MICHAEL MOSLEY: My brilliant BBC friend Jana Bennett – and the bran cancer discoveries I’m hoping can save her

Half of us will develop cancer at some point in our lives. It’s a statistic that often frightens people. But there’s good news, which makes the figures far less scary… thanks to medical advances, the chances of surviving cancer are now pretty good.

One of the most promising of recent developments has been immunotherapy treatments, that galvanise the body’s immune system to attack cancers.

But are any of these medical innovations cures? It’s too early to say. Most doctors still don’t like to talk about ‘curing cancer’.

Former BBC executive Jana Bennett was recently diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, the same tumour that led to the death of former Labour Minister Tessa Jowell last year

Instead, they prefer to talk about five-year survival rates – your chance of living for five years after the original diagnosis. In recent years, five-year survival rates for common cancers, such as breast, bowel and prostate, have all shot up, especially in cases where it is diagnosed early.

One exception is brain cancer, for which the five-year survival rate is just five per cent.

I decided to write about brain cancer in support of a friend of mine, former BBC executive Jana Bennett, who was recently diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, the same tumour that led to the death of former Labour Minister Tessa Jowell last year.

Jana announced her illness last week at the launch of a new brain cancer charity called OurBrainBank, which she is supporting. It provides patients with a smartphone app, enabling them to share their knowledge and experiences with other patients. The anonymous information is then shared with scientists worldwide to speed up research.

But what are the current options for brain cancer patients such as Jana? And is there anything else on the horizon?

These days you can chat during surgery

More than 2,000 Britons are diagnosed with glioblastoma – the most common primary brain tumour – every year. It’s primary because it starts in the brain, as opposed to being a cancer elsewhere in the body that spreads to the brain. Given the scarcity of effective treatments, many glioblastoma patients immerse themselves in the scientific literature to see if they can improve their odds.

Jana is particularly well-placed to do this – she was once head of the BBC science department. She was my charismatic boss for many years, and masterminded several TV classics, including Walking With Dinosaurs, The Human Body and Animal Hospital, and even won an OBE for services to science broadcasting

Jana first realised something was wrong when friends told her that she had started sending them garbled texts and emails a few months ago. Then she began to have problems walking.

She went to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, where scans revealed the bad news: she had a glioblastoma.

‘I was obviously shocked,’ she told me, ‘but I realised I would just have to get on with it.’

The surgical approach to removing brain tumour is extraordinary, because during the operation the patient is wide awake.

So-called ‘awake brain surgery’ yields the best results because, keeping the patient awake and able to chat means the surgeon can get as much of the cancer out as possible, while minimising the risk of damaging something important, like speech.

I’ve been present at a couple of these operations, and they are unsettling. The patient lies on the operating table with a hole in their skull and their brain exposed, yet chatting away, about the weather, say, or the football scores. If the patient starts to slur, or can’t answer questions, the surgeon knows they are getting too close to a vulnerable area – and backs off.

Jana’s operation took more than eight hours, and she was fully conscious throughout. Surgery was followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. So far the signs are good. The problem is that glioblastomas often grow back – which is the challenge for researchers.

There are, however, a few experimental options in progress…

The skull cap that zaps cancer cells

Former Labour cabinet minister Tessa Jowell lost her battle with glioblastoma last year. She used the Optune device during her treatment against the disease

One is a new device called Optune, which sticks to the head.

The wearable gadget is said to limit the ability of cancer cells to divide and spread by applying electrical stimulation across the brain, transmitted by in-built ceramic discs and powered by a portable battery.

It’s not available on the NHS but evidence for its effectiveness comes mainly from a medical trial involving more than 300 patients who’d had brain surgery to remove a glioblastoma. The patients were either allocated to standard treatment or treatment plus Optune.

Nearly a third of the patients who used Optune at least 90 per cent of the time survived for more than five years.

This is impressive when compared with the standard five-year survival rate, which is just five per cent of patients.

Fighting cancer with your own immunity

But the innovation that excites me the most is immunotherapy.

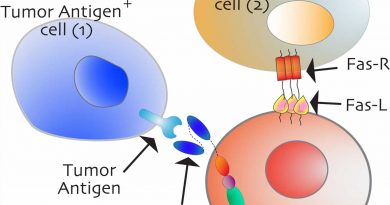

It truly is one of the brightest hopes for anyone who is diagnosed with cancer in 2019. The idea is that the body’s immune system is mobilised to attack the cancer, just as it would an infection. We’ve seen success in an array of cancers – but what about those that affect the brain?

The challenge is the existence of the blood-brain barrier, which stops cancer-fighting compounds, such as those in chemotherapy, from accessing the tumour deep within the brain.

The cells of your immune system can get through this barrier, but brain cancers are masters at hiding away.

Immunotherapy is the idea that the body’s immune system is mobilised to attack the cancer, just as it would an infection

So researchers are studying ways to teach the immune system how to spot a tumour. One method involves harnessing dendritic cells, part of the immune system.

The job of these cells is to identify the enemy, or the tumour, so that other parts of the immune system can attack.

To ‘teach’ dendritic cells what to look for, they are extracted from the patient, then mixed with cells taken from the patient’s tumour, removed during surgery.

The researchers inject these activated dendritic cells back into the patient, hoping they will reach the brain then recognise and help kill the tumour. Results from early studies look promising.

Do you have a question for Dr Mosley?

Email [email protected] or write to him at The Mail on Sunday, 2 Derry Street, London W8 5TT.

Dr Mosley can only answer in a general context and cannot give personal replies.

Another form of immunotherapy involves something called ‘checkpoint inhibitors’.

Cancers can often protect themselves against the immune system by producing chemicals that turn off our fighting cells.

Checkpoint inhibitors block the action of these chemicals, switching the immune system back on.

These drugs have worked well in some skin and lung cancers. The hope is that they will also help with brain cancer, but the research is ongoing. Otherwise, if you have cancer, it’s important to live as healthy as you can.

Jana is eating well, getting plenty of exercise and staying hopeful.

‘What’s wonderful,’ she told me, ‘is researchers are finding lots of ways to stimulate a patient’s immune system to fight their own tumour. I am feeling cautiously optimistic.’

- For more information about brain cancer, visit ourbrainbank.org and thebraintumourcharity.org.

Source: Read Full Article