Clinicians May Not Prescribe New Postpartum Depression Drug

A new drug for postpartum depression (PPD) is expected to be available to prescribers by early next year, but whether clinicians will prescribe the medication, and to whom, depends on how insurers cover the drug.

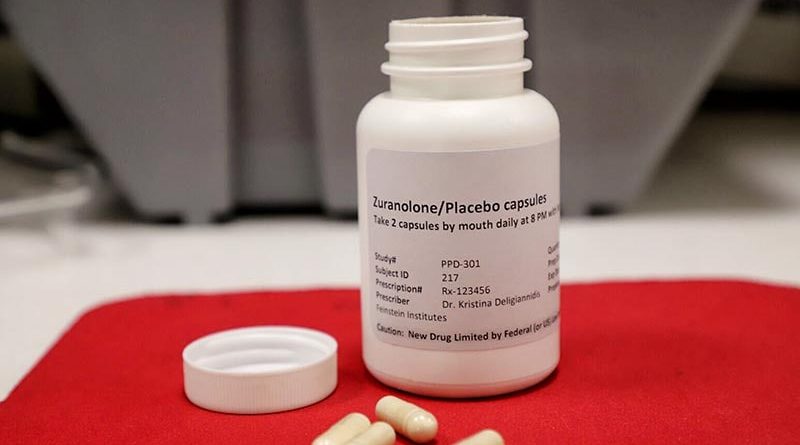

The expected cost of zuranolone — nearly $16,000 for a 14-day course — could make it inaccessible to many patients.

Some providers see the drug as promising, but they also need more information on how safe the drug will be for infants of breastfeeding parents and if the effects of treatment last more than 2 weeks.

“I’m definitely not in the camp of ‘absolutely would not prescribe.’ I think this medication has a lot of potential benefits,” said Leena P Mittal, MD, chief of the Division of Women’s Mental Health, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. But “there is still a lot of information that is yet to be known or clarified in terms of how and to whom we prescribe this medication.”

Zuranolone, from Biogen and Sage Therapeutics, has been hailed by clinicians for the results from clinical trials that show the drug quickly relieves PPD. But questions remain about how insurance companies pay for the drug and how the manufacturers will make the drug more affordable for out-of-pocket payers.

“If cost is a barrier, you could widen disparities to a clinical problem that already disproportionately affects people who have less access to traditional treatments like therapy,” said Kirstin E Leitner, MD, assistant professor of Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, Penn Medicine, Philadelphia.

In an emailed statement, Matthew Henson, a spokesperson for Sage Therapeutics, told Medscape Medical News the company expects to share plans for patient support programs in December. Who those programs will benefit is unclear.

“Sage and Biogen plan to have support services and financial assistance programs available” for patients who meet certain requirements, Henson said. “Coverage across all payor segments traditionally takes time. Sage and Biogen are committed to addressing any access gaps for patients starting on day one.”

Henson also said the companies will address racial inequities that underpin disparities in access to mental health services among patients with PPD.

“We also know that Black and Brown women are disproportionately impacted, and we are prioritizing equitable access, as well as advocating for policies that better support underrepresented communities,” he said.

Henson did not respond to questions regarding how the drug company landed on the nearly $16,000 price tag for the regimen.

The drug makers originally sought approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for zuranolone as a treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), but the agency denied the request.

In an August press release, Sage noted the FDA said, “the application did not provide substantial evidence of effectiveness to support the approval of zuranolone for the treatment of MDD and that an additional study or studies will be needed.”

Some analysts speculate that because the drug will be available to a much smaller portion of people –– those with PPD rather than anyone with MDD –– the drug companies raised the cost.

Early Data Look Good, but Providers Want More on Long-Term Efficacy and Breastfeeding

Zuranolone is approved as a 14-day daily oral treatment of PPD. So far, data show the drug can start relieving symptoms in as little as 3 days.

“The rapidity of action of medication could be hugely effective,” Mittal said. “If there was someone who would be able to pay out of pocket, the characteristics of the medication don’t make me hesitant to prescribe it, necessarily; there’s just a lot more to be known.”

But cost isn’t the only concern for clinicians. Some prescribers want more data on taking zuranolone while breastfeeding, as well as additional studies on efficacy well after treatment has ended. Mittal said the most recent study followed participants for only 45 days after treatment ended.

“It seems like it had wonderful efficacy, but the durability of the treatment’s effect is less clear,” Mittal said. “We also have very little data on breastfeeding. Those are some areas where I have some hesitancy, not just the cost.”

Another drug from Sage, brexanolone (Zulresso), was approved in 2019 but is twice as costly as zuranolone. Both medications work by modulating the gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors affected by pregnancy hormones, which are believed to be a driver of PPD.

“Brexanaolone was really ground-breaking in many ways because it was the first medication for this indication and particular mechanism, but for a variety of reasons, it didn’t have a big impact in terms of practice,” Mittal said.

Brexanolone is administered through a 60-hour IV infusion and requires a hospital stay, making the drug inaccessible for many patients due to both cost and time.

The set, temporary course of treatment could make zuranolone more appealing to some patients than traditional antidepressants, Leitner said.

“Some people are hesitant to start traditional antidepressants because they are afraid they will struggle to get off of them,” she said.

One, Not the Only, Option

That zuranolone is both cheaper than brexanolone and can easily be taken at home are both significant benefits to the medication, according to Ashlie D Butler, DNP, mental health nurse practitioner, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY, who specializes in women’s health. She said zuranolone may be the best option for a subset of patients with PPD. In those cases, she would prescribe it.

“I think it could be well suited for people with severe depression that’s affecting their ability to care for or bond with their baby or who are experiencing suicidality,” she said, adding that she envisions herself prescribing zuranolone to patients who have no history of depression and who have serious symptoms. “In those cases, it’s more likely that it’s a hormonal cause.”

For postpartum patients who have a history of depression, Butler said traditional antidepressant medications should be a first-line treatment, especially if specific drugs have been effective for a patient in the past.

“There are other medications that are not approved by the FDA for PPD but that we use all the time which are more accessible and less costly,” Butler said.

These medications, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, can take as long as 6 weeks to take effect, so this route would be appropriate only for patients who are not experiencing severe symptoms, she said.

“This is a good place to start, especially if they’ve been on them with success before pregnancy,” she said. “But for those who can’t get out of bed, can’t feed their baby, or are suicidal, we need to act faster.”

Source: Read Full Article