Californias Highest COVID Infection Rates Are In Rural Counties

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of covid-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new covid infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new covid cases and more than two dozen covid-related deaths per day. So, where does covid continue to simmer in California? And why?

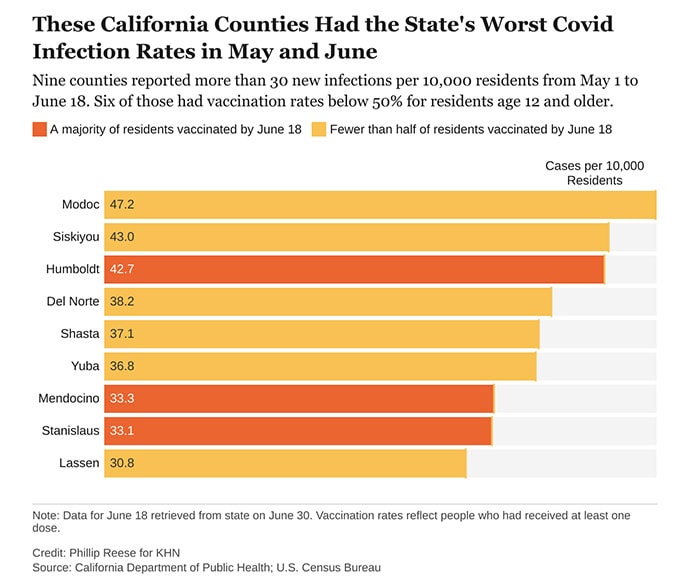

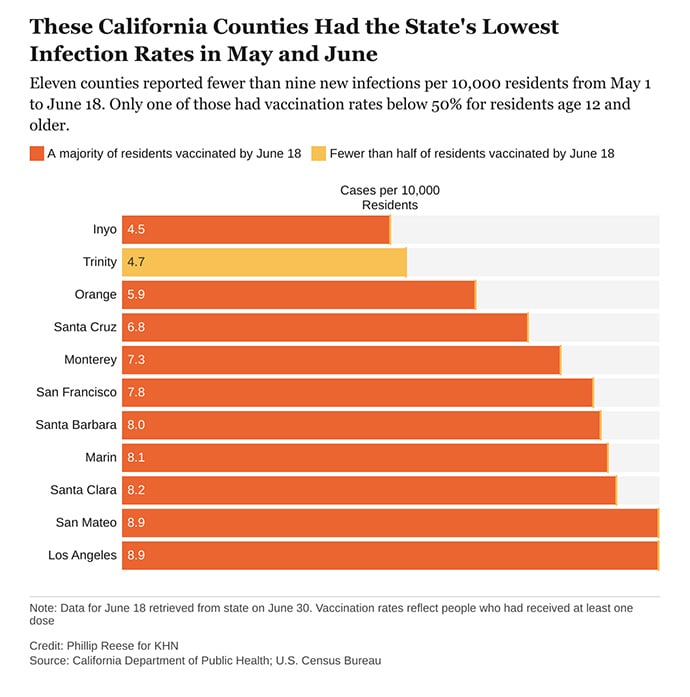

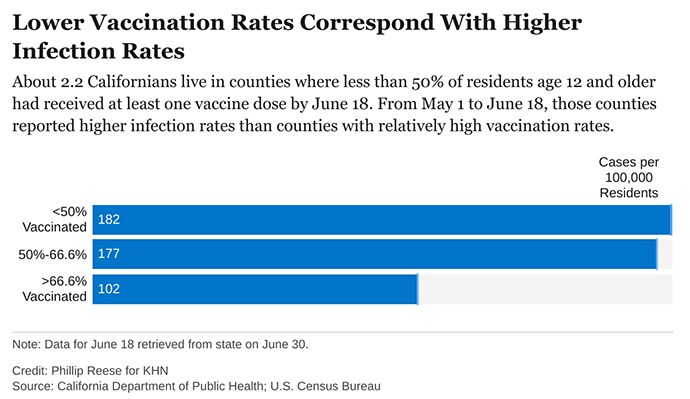

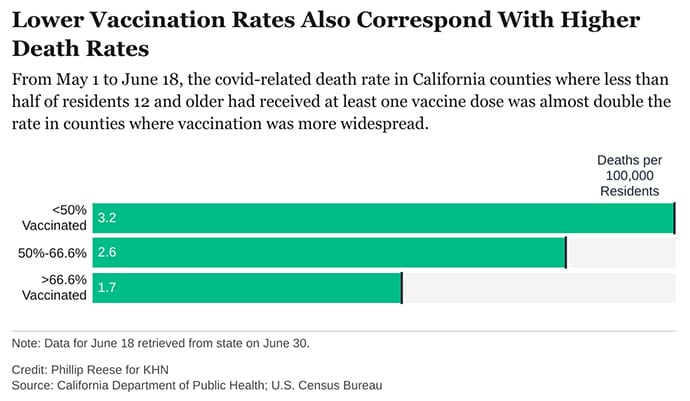

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of covid infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new covid infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data shows. By comparison, there were about 102 covid infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine. Burke noted that the highly contagious delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in covid-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 covid-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates — Trinity and Mariposa — also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates — among them Sonoma and Contra Costa — had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said Dr. George Rutherford, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California-San Francisco. “One is the vaccine — very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of covid vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s covid infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s five minutes from your house,” Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as covid reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already,” Rutherford said.

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California-Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

Phillip Reese is a data reporting specialist and an assistant professor of journalism at California State University-Sacramento.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Source: Read Full Article