A new target identified to combat a dangerous Melioidosis infection

Researchers at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology—Hans Knöll Institute (Leibniz-HKI) in Jena, Germany have identified an enzyme that is a promising new therapeutic target to combat the dangerous bacterial disease melioidosis. It helps the pathogenic bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei construct a toxic molecule that is critical in the infection process. The results were published in Nature Chemistry.

Melioidosis is a life-threatening disease caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. “Without treatment, the disease is usually fatal,” Christian Hertweck, head of the Biomolecular Chemistry Department at Leibniz-HKI and professor of natural product chemistry at Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, explains. “And even antibiotic treatment often drags on for many months and is not always successful because common drugs do not work well against these pathogens.”

His research group therefore wanted to understand the bacterium’s infection mechanisms and has come across a possible new starting point for combating the disease. “We have found an enzyme that synthesizes a molecular structure central to the infection,” explains Felix Trottmann, first author of the study.

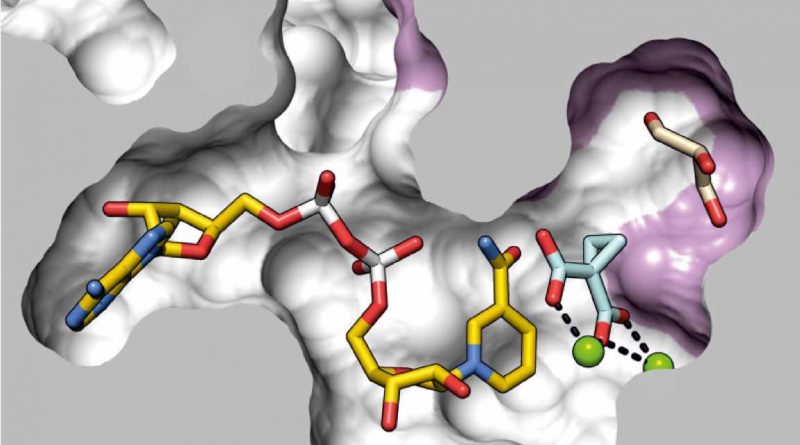

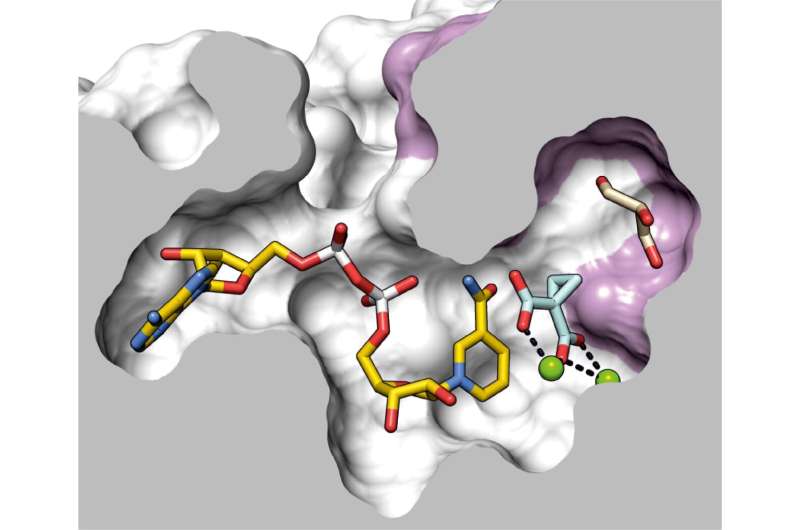

The discovered enzyme BurG forms a cyclopropanol ring, a highly reactive chemical functional group, from a precursor molecule. In previous studies, Trottmann was able to demonstrate that this structure is also produced by other pathogenic bacteria in the genus Burkholderia and apparently has an important role in infection. If the biosynthetic pathway for this molecule is switched off by mutations, the bacteria are far less dangerous.

The research team has also elucidated the 3D structure of the enzyme in cooperation with TU Munich. “In a next step, we can now try to design active compounds that inhibit the enzyme and thus make the bacteria less virulent,” Trottmann explains. According to current knowledge, the enzyme is only found in bacteria and not in humans. “The hope is therefore to be able to specifically inhibit the bacteria,” says Hertweck. The immune system could then deal with them more easily.

To understand the biosynthesis of the molecular structure central to infection, the researchers investigated the gene cluster that contains the DNA instructions for making it. They conducted the laboratory experiments using Burkholderia thailandensis, which is very similar to Burkholderia pseudomallei but is much safer to work with.

Source: Read Full Article